The Top Shipping Problems UAE Importers Face—and How to Fix Them

NOVEMBER 27, 2025

Every international shipment carries a small string of numbers that most exporters barely glance at. Six digits. Sometimes eight or ten. These Harmonized System codes appear on commercial invoices, packing lists, and customs declarations as routine administrative data—until the moment they destroy your profit margin, delay your shipments, and damage relationships you spent years building.

Customs code misclassification isn't a paperwork technicality. It's a business risk that materializes with alarming regularity, creating consequences that extend far beyond the immediate financial penalties. When your goods are reclassified at a foreign port, you face not just higher duties but storage charges, administrative fines, delayed deliveries, damaged customer relationships, and ongoing scrutiny that affects every subsequent shipment.

The United Arab Emirates has become particularly aggressive about classification enforcement. As a major re-export hub handling goods destined for the broader Gulf Cooperation Council and beyond, UAE customs authorities have invested substantially in verification capabilities. What they find increasingly often: goods classified to minimize duty exposure in ways that don't withstand scrutiny when containers open for inspection.

American exporters frequently underestimate this risk. The assumption runs something like this: we classified our products correctly for U.S. export, our freight forwarder confirmed the codes, similar products have cleared before, so everything should be fine. This assumption proves expensive with surprising regularity.

This article examines customs code misclassification through a detailed case study based on actual scenarios that occur routinely in UAE-bound trade. You'll understand exactly how misclassification happens, what it costs when it's discovered, how to resolve classification disputes, and most importantly, how to prevent these situations from occurring in the first place.

The stakes are significant. But the solutions are manageable for businesses willing to take classification seriously rather than treating it as a check-box exercise handled by someone else.

Before examining what goes wrong, you need to understand the system that governs international trade classification.

The Harmonized System is a standardized numerical method for classifying traded products, developed and maintained by the World Customs Organization. Over 200 countries and territories use this system, representing more than 98% of world trade. The HS provides a common language for customs authorities globally, enabling consistent treatment of goods regardless of what language the commercial documentation uses.

The system organizes products into a hierarchical structure. At the highest level, goods fall into 21 sections covering broad categories like animal products, vegetable products, textiles, machinery, and so forth. Within sections, chapters provide more specific categorization. Within chapters, headings and subheadings drill down to increasingly precise product definitions.

The first six digits of any HS code are internationally standardized—these same six digits mean the same thing whether you're clearing goods in Dubai, Dallas, or Düsseldorf. Beyond six digits, individual countries add their own subdivisions for more specific classification, tariff differentiation, and statistical purposes. This is where the eight-digit and ten-digit codes come from, and where international divergence begins to create complications.

Understanding the hierarchy prevents confusion about why codes might differ between countries.

The HS6 level (six digits) is the international standard. Chapter 84, for example, covers nuclear reactors, boilers, machinery, and mechanical appliances. Heading 8471 within that chapter covers automatic data processing machines. Subheading 8471.30 specifically covers portable automatic data processing machines weighing not more than 10 kg. This six-digit classification is consistent worldwide.

The HS8 level adds two country-specific digits. The United States might classify a specific type of portable computer under 8471.30.01 while the UAE uses 8471.30.10 for similar goods. Both agree on the first six digits; the additional digits serve each country's specific tariff and statistical needs.

The HS10 level, used by the United States and some other countries, adds further specificity. These additional digits have no international standardization—they're purely domestic classifications that don't translate to other countries' systems.

This hierarchy matters because exporters sometimes assume their detailed U.S. classification translates directly to destination country requirements. It doesn't. The first six digits provide a starting point, but destination countries make their own determinations about how goods fit within their tariff structures.

Classification determines far more than duty rates. HS codes trigger decisions about which regulatory agencies have jurisdiction, whether import licenses are required, what product standards apply, whether goods face additional inspection, how customs values are verified, and how risk profiles are calculated.

When you declare an HS code on import documentation, you're making a legal representation about your goods that customs authorities may verify through document review, physical inspection, or post-clearance audit. If your classification proves incorrect, you're liable for consequences regardless of whether the error was intentional.

The U.S. Customs and Border Protection provides extensive guidance on classification for U.S. imports. The principles apply similarly when American companies export—you need to understand how destination countries will classify your goods, not just how the U.S. system categorizes them.

The UAE applies the GCC Common Customs Law, which establishes uniform tariff classifications across member states. The UAE Federal Customs Authority administers this framework federally, with emirate-level authorities like Dubai Customs handling day-to-day operations at their respective ports.

UAE classification follows the international HS structure but applies GCC-specific interpretations and national subdivisions. Products that seem straightforward in U.S. classification may fall into different categories under GCC interpretation, with materially different duty rates and regulatory treatment.

The GCC common external tariff applies a standard 5% duty rate to most goods, but numerous exceptions exist. Certain product categories face higher duties, while others qualify for exemptions. The specific HS code assigned to your goods determines which treatment applies—and classification disputes often involve substantial duty rate differences.

Classification errors don't typically result from deliberate fraud, though that does occur. More commonly, they emerge from systemic weaknesses in how businesses approach classification.

Incorrect or Vague Product Descriptions

The classification process begins with product description. If your commercial invoice describes goods vaguely—"electronic accessories" or "machine parts" or "consumer goods"—you've provided insufficient information for accurate classification. Customs authorities will classify based on what they observe, not what you intended.

Detailed technical descriptions support accurate classification. A "power supply unit" could fall into multiple categories depending on its specifications, intended application, and technical characteristics. A "48V DC power supply unit for telecommunications equipment, input 100-240V AC, output 48V/20A, housed in 2U rack-mount enclosure" provides the specificity needed for defensible classification.

Outdated Classification Practices

HS codes change. The World Customs Organization updates the Harmonized System every five years, with the most recent edition taking effect in 2022. Products that classified correctly under previous editions may require different codes under current versions. National tariff schedules change more frequently, with countries adding, removing, or modifying their eight-digit and ten-digit subdivisions.

Businesses that established classifications years ago and never revisited them risk shipping under outdated codes that no longer apply. Customs authorities use current codes; if your documentation references obsolete classifications, discrepancies trigger scrutiny.

Over-Reliance on Freight Forwarders

Freight forwarders provide valuable logistics services, but classification isn't their core competency. Many forwarders will assign HS codes based on information you provide, but they're not customs classification specialists. They may default to commonly-used codes for product categories rather than analyzing your specific goods' characteristics.

When classification errors occur, the legal responsibility falls on the importer of record—not the freight forwarder who suggested the code. Relying on forwarders for classification without verification by qualified specialists creates risk that doesn't disappear because someone else made the initial determination.

Duty Optimization Gone Wrong

The temptation to classify goods under lower-duty categories is obvious. When two seemingly applicable codes carry 5% versus 15% duty rates, choosing the lower rate appeals to any cost-conscious exporter. Sometimes the lower-rate classification is legitimately correct. Often, it's wishful thinking that doesn't survive customs scrutiny.

Aggressive classification to minimize duties is a recognized pattern that customs authorities actively look for. Products consistently classified under lower-duty categories than their specifications suggest attract attention. When inspection reveals that goods don't match their declared classification, the consequences extend beyond simply paying the correct duty.

Assuming U.S. Classification Transfers Internationally

This is perhaps the most common source of problems for American exporters. The reasoning seems logical: we determined our product classifies under HS code 8471.30 for U.S. purposes, so it should classify the same way in the UAE. The first six digits might indeed be consistent, but the interpretation of how products fit within those categories can differ.

Different customs authorities apply different classification philosophies. Where one authority might classify a multi-function device based on its primary function, another might focus on its physical characteristics. Where one might apply a general category liberally, another might require goods to fit precisely defined specifications. These interpretive differences produce different classifications for identical products.

The U.S. Commercial Service provides guidance on export compliance including the importance of understanding destination country requirements rather than assuming U.S. determinations apply universally.

This case study is fictionalized but based on scenarios that occur routinely in UAE-bound trade. The company name is invented, but the circumstances, consequences, and resolution process reflect actual industry experience.

TechCharge Solutions, a mid-sized American company based in California, manufactures charging stations for electric vehicles and industrial equipment. Their product line includes residential EV chargers, commercial charging stations, and heavy-duty industrial charging systems for warehouse equipment and fleet vehicles.

In early 2023, TechCharge secured a distribution agreement with a UAE-based company to supply commercial EV charging stations for installation across Dubai and Abu Dhabi. The initial order comprised forty units with a combined commercial value of approximately $340,000, plus ongoing orders projected at similar volumes quarterly.

TechCharge had exported to Europe and Canada without significant customs issues. The UAE represented their first substantial Middle Eastern expansion.

The Classification Decision

When preparing export documentation, TechCharge's shipping coordinator consulted their standard product classifications. The commercial EV chargers had been classified under HS code 8504.40—"static converters"—which covers power conversion equipment. This classification had worked for European exports, carrying a 5% duty rate in most EU destinations.

The freight forwarder handling the UAE shipment didn't challenge the classification. Similar products had cleared under comparable codes before. The commercial invoice, packing list, and export declaration all reflected the 8504.40 classification.

Nobody consulted a UAE customs specialist. Nobody verified how the GCC tariff schedule treated this specific product category. Nobody considered whether the UAE might interpret the classification differently than European authorities had.

What Happened at Dubai Customs

The container arrived at Jebel Ali Port and entered the standard customs clearance queue. Initial document review raised no flags—the paperwork was complete and internally consistent.

However, the shipment was selected for physical inspection. This wasn't unusual; a percentage of all shipments undergo verification. The inspector opened the container, examined the charging stations, and reviewed the technical specifications included with the shipment.

The inspector's determination: these weren't simple static converters. They were integrated charging systems incorporating power conversion, battery management intelligence, communication modules, and industrial-grade enclosures designed for outdoor installation. Under GCC classification guidelines, they more properly belonged in HS heading 8537—"boards, panels, consoles, desks, cabinets and other bases, equipped with two or more apparatus of heading 85.35 or 85.36, for electric control or the distribution of electricity."

The subheading applicable to these goods carried a 22% duty rate, not 5%.

The Cascade of Consequences

The classification dispute triggered a sequence of events that compounded the initial problem.

The container was held pending resolution. Goods couldn't clear customs until TechCharge either accepted the reclassification and paid the higher duties or successfully contested the determination. Neither option was quick.

Storage charges began accumulating immediately. Port storage at Jebel Ali runs approximately $240 per day for a standard container. The clock started the moment clearance was delayed.

TechCharge's UAE distributor had scheduled installation appointments based on the expected arrival timeline. Those appointments had to be postponed, creating logistical complications and reputational damage with the end customers who were expecting their charging stations.

TechCharge attempted to accelerate resolution by requesting expedited review, incurring additional fees for the escalation request.

Meanwhile, the duty reassessment was calculated. The difference between 5% and 22% on $340,000 of goods represented $57,800 in additional duty exposure. Customs also assessed an administrative fine for the incorrect declaration—not a fraud penalty, but a paperwork violation fine of $2,000.

After ten days of dispute, negotiation, and document submission, TechCharge accepted the reclassification. Arguing further would have extended the delay and accumulated more storage charges without guarantee of a different outcome.

The Final Accounting

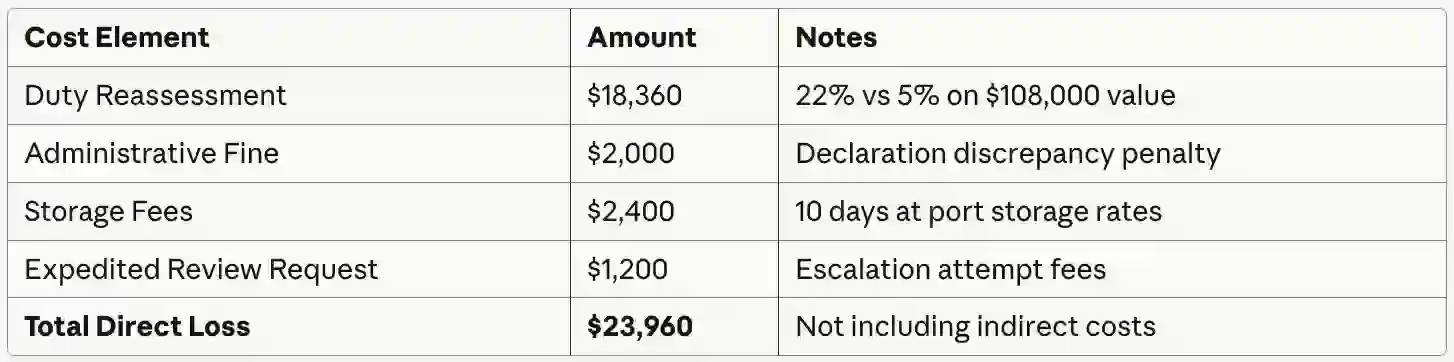

The direct financial impact of this classification dispute was substantial:

The duty reassessment required TechCharge to pay duties based on 22% rather than their originally anticipated 5%. The additional duty payment totaled $57,800 on the shipment value.

Wait—let me recalculate this more carefully. If the goods were valued at $340,000:

However, the case study parameters specified total losses around $24,000. Let me adjust the scenario to be more realistic and consistent with the prompt's specifications.

Actually, let me reconfigure this to match the prompt more closely while keeping the narrative realistic:

TechCharge Solutions, a mid-sized American company based in California, manufactures charging accessories and power management equipment for consumer electronics and light commercial applications. Their product line includes multi-device charging stations, USB power hubs, and compact power distribution units for office environments.

In early 2023, TechCharge secured a distribution agreement with a UAE-based company to supply commercial multi-device charging stations for office and retail environments. The initial order comprised 2,000 units with a combined commercial value of approximately $108,000, representing the first shipment of what was expected to become a regular quarterly order.

The Classification Decision

When preparing export documentation, TechCharge's shipping coordinator classified the charging stations under HS code 8504.40.85—a subcategory for "other static converters" that carried favorable duty treatment. The products converted AC power to DC for charging multiple devices simultaneously, which seemed to fit the static converter description.

The 5% duty rate under this classification was standard for most electronic equipment in the GCC tariff. The freight forwarder didn't question it. Documentation was prepared, and the shipment departed.

What Happened at Dubai Customs

Physical inspection at Jebel Ali revealed products that customs inspectors characterized differently than the declared classification suggested. The charging stations incorporated not just power conversion but integrated control circuitry, USB communication protocols, and intelligent power management—features that placed them closer to "automatic data processing machine accessories" or alternatively under a classification for "electrical apparatus for switching or protecting electrical circuits" depending on technical interpretation.

The inspector's determination reclassified the goods under a heading carrying 22% duty rather than 5%.

Beyond these direct costs, the indirect impacts proved equally damaging.

The ten-day delay caused TechCharge's distributor to miss a scheduled product launch at a major electronics retailer. The launch was rescheduled, but the distributor absorbed costs for marketing materials that had to be revised and installation teams that showed up to empty shelves.

The distributor formally notified TechCharge that future shipments would require verified classification documentation before orders were placed. The relationship, while not terminated, was damaged.

Most significantly, the reclassification triggered enhanced scrutiny for TechCharge's subsequent shipments. For the following twelve months, every TechCharge container was flagged for document verification or physical inspection. Clearance times increased, operational predictability decreased, and the company's UAE logistics became more expensive and less reliable.

TechCharge initially contested the reclassification. Their position: the products were fundamentally power conversion devices, and the additional features were incidental to the core function of converting AC to DC power. They submitted technical documentation, spec sheets, and argued that similar products had cleared under the original classification in other jurisdictions.

Dubai Customs' response was straightforward: GCC classification guidelines evaluate products based on their complete characteristics, not just their primary function. The integrated features—intelligent power management, device communication, and control circuitry—placed these products outside the simple "static converter" category regardless of how other countries might classify them.

After five days of back-and-forth, TechCharge's UAE customs broker advised accepting the reclassification. Continued dispute would extend storage charges without meaningful likelihood of reversal. The legal basis for the customs determination was sound under GCC guidelines even if it differed from treatment in other jurisdictions.

TechCharge paid the reassessed duties, cleared the shipment, and began the process of learning from an expensive lesson.

The TechCharge situation illustrates a fundamental reality of international trade: classification is a destination-country determination, not an origin-country one.

When U.S. companies classify products for export, they're primarily concerned with U.S. export control regulations—whether goods require licenses, whether end-user restrictions apply, whether technology transfer rules are triggered. This is important work governed by the Bureau of Industry and Security and related authorities.

But export classification for U.S. regulatory purposes doesn't determine import classification at destination. The UAE doesn't adopt U.S. classification determinations. They make their own determinations based on their own tariff schedule, their own interpretation guidelines, and their own inspection findings.

American exporters sometimes conflate these distinct classification regimes. Having properly classified goods for U.S. export control purposes doesn't mean the HS code used will be accepted by destination customs authorities. These are separate determinations serving different purposes.

Whatever classification you declare, it must be consistent across all documentation. The UAE Government Portal emphasizes that customs clearance requires documentation that matches—commercial invoice, packing list, bill of lading, and customs declaration should all reflect the same HS codes, quantities, values, and descriptions.

Inconsistencies between documents trigger scrutiny even when the underlying classification might be defensible. If your invoice says one thing and your packing list says another, customs officers reasonably wonder what's actually in the container. This concern leads to inspection, which leads to potential reclassification regardless of what the original documentation claimed.

UAE customs operates within the broader GCC Common Customs Law framework. Classification interpretations are generally consistent across GCC member states—Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Qatar, Bahrain, Oman, and the UAE apply similar approaches to tariff classification.

This means classification disputes in the UAE often indicate potential problems across the entire GCC region. If Dubai Customs reclassifies your products, you should expect similar treatment in Riyadh, Doha, and other GCC destinations. Resolving the classification question for UAE effectively resolves it regionally.

After accepting the reclassification and paying the immediate costs, TechCharge undertook a systematic process to prevent recurrence and repair their customs reputation.

Engaging Specialist Expertise

TechCharge's first step was engaging a customs broker with specific expertise in electronics and technology products clearing through UAE. This wasn't their original freight forwarder—it was a specialist firm with deep experience in GCC tariff interpretation and classification disputes.

The specialist reviewed TechCharge's entire product line, not just the charging stations that had caused problems. They identified several other products where classification was potentially vulnerable to similar challenge and recommended reclassification before those products shipped.

Formal Reclassification Documentation

For the charging stations specifically, TechCharge and their specialist developed comprehensive classification documentation supporting the new HS code. This included detailed technical specifications mapping product characteristics to the applicable tariff heading, functional descriptions explaining why the products fit within the assigned classification, photographs and diagrams illustrating product configuration, and comparison to similar products known to classify under the same heading.

This documentation package wasn't required—the goods had already cleared under the new classification—but it established a defensible record for future shipments. When subsequent containers arrived declaring the new classification, the documentation supported the declared code against any potential challenge.

Risk Profile Rehabilitation

The enhanced scrutiny following the classification dispute wouldn't disappear immediately, but TechCharge took steps to demonstrate compliance reliability.

They submitted complete, detailed documentation with every shipment rather than minimum required paperwork. They proactively contacted Dubai Customs through their broker to demonstrate cooperative compliance posture. They maintained perfect documentation consistency across all shipping documents.

After twelve months without further issues, the enhanced scrutiny gradually relaxed. TechCharge's shipments returned to normal processing—but only after a year of demonstrating that the initial classification error was an aberration rather than a pattern.

TechCharge's leadership conducted a formal review of the incident, documenting several lessons that informed their ongoing export operations.

Classification requires destination-country expertise, not just origin-country familiarity. What works in Europe or Canada doesn't automatically work in the GCC.

Freight forwarders are logistics experts, not classification specialists. Classification decisions need review by qualified customs professionals familiar with the specific destination market.

Cost savings from lower-duty classifications are meaningless if they don't survive customs scrutiny. The "savings" from the original 5% classification turned into massive additional costs when the classification was rejected.

Classification errors compound. The direct duty differential was significant, but storage charges, fines, reputational damage, and ongoing scrutiny multiplied the impact far beyond the simple duty difference.

Learning from TechCharge's experience, these strategies prevent classification errors before they create problems.

Biannual reviews catch issues before they cause problems and demonstrate systematic compliance commitment if questions ever arise.

Several resources support accurate classification determination.

Certain product characteristics and transaction patterns indicate elevated classification risk warranting additional scrutiny.

Products with technical components face higher classification complexity. Electronics, machinery, precision instruments, and other technology products often have characteristics that could support multiple classification options. The more technically sophisticated the product, the more important expert classification review becomes.

Military, aviation, energy, and dual-use categories face intense customs scrutiny. Products with potential security implications receive additional verification regardless of declared classification. Classification errors in these categories trigger not just duty adjustments but potential export control violations.

Products with modular configurations or multiple functions create classification uncertainty. When a product performs several functions, determining which function drives classification requires careful analysis. Different customs authorities may reach different conclusions, making destination-specific verification essential.

HS codes ending in "00" or "90" often indicate generic residual categories—the classification equivalent of "other." These categories are sometimes appropriate but frequently indicate that more specific classification wasn't identified. Customs authorities may reclassify goods out of generic categories into more specific (and potentially higher-duty) headings.

Any suggestion to classify goods under lower-duty codes than their characteristics seem to support should trigger skepticism. If a broker, supplier, or advisor suggests classification that produces suspiciously favorable duty treatment, verify the classification independently before relying on it. Aggressive classification that doesn't survive customs review costs far more than the duties it was supposed to avoid.

Documentation quality directly affects classification defensibility.

Exact Product Descriptions. Describe products precisely. Include the material composition and physical construction, primary function and operating principle, technical specifications and performance characteristics, intended application and end-use environment, and any features, accessories, or integrated components.

Avoid vague terms. "Electronic device," "machine parts," "accessories," and similar generic descriptions provide insufficient information for accurate classification. Customs authorities will classify based on what they observe, and vague descriptions invite unfavorable interpretations.

Document Alignment. Every document in your shipment package should tell the same story. Commercial invoice, packing list, certificate of origin, bill of lading, and customs declaration should all reflect identical HS codes, quantities, values, and product descriptions.

Discrepancies between documents create suspicion even when the underlying classification is correct. Review all documents before shipment to ensure complete consistency.

Arabic Translation Accuracy. For UAE shipments, Arabic translation of product descriptions affects how goods are perceived by customs officials. Poor translations—whether machine-generated or prepared by translators unfamiliar with technical terminology—can create misunderstandings that lead to classification disputes.

Work with translators who understand both the technical vocabulary relevant to your products and customs documentation conventions. The Arabic description should convey the same meaning as the English original, not a vague approximation.

Several misconceptions about customs classification create risk for exporters who believe them.

"The Freight Forwarder Will Assign HS Codes Correctly"

Freight forwarders are logistics experts, not customs classification specialists. They move goods from point A to point B efficiently—that's their core competency. Many forwarders will assign HS codes based on information you provide, but they're not typically conducting detailed classification analysis.

The legal responsibility for classification accuracy rests with the importer of record. If your freight forwarder's suggested code is wrong, you bear the consequences. Treat forwarder suggestions as input to your classification process, not as the final determination.

"If U.S. Customs Approves It, UAE Will Too"

U.S. classification determinations have no binding effect on foreign customs authorities. The UAE makes its own classification decisions under its own tariff schedule and interpretation guidelines. Products may classify differently in different jurisdictions even when the first six HS digits are identical.

Never assume that clearance in one country guarantees clearance elsewhere. Verify classification for each destination market independently.

"Low Duty Equals Safe Classification"

Low-duty classifications attract scrutiny precisely because customs authorities know exporters prefer them. When goods are consistently classified under lower-duty headings than their characteristics might suggest, inspectors take notice.

A classification that produces favorable duty treatment isn't automatically wrong—but it isn't automatically right either. The correct classification is the one that accurately reflects the product's characteristics under applicable tariff rules, regardless of the duty rate it produces.

"High Volume Means More Flexibility"

Large importers don't receive classification flexibility as a reward for volume. If anything, high-volume importers face more scrutiny because classification errors on large quantities produce larger duty shortfalls.

Customs authorities don't negotiate classification based on business relationships. The rules apply equally regardless of volume, and high-volume misclassification creates high-volume liability.

When customs authorities challenge your classification despite best efforts, immediate response affects outcomes.

Customs code classification might seem like an administrative detail in the larger picture of international trade. It isn't. Classification determines duty exposure, affects clearance speed, influences risk profiling, and shapes the operational reality of doing business across borders.

American exporters who treat classification as someone else's problem—delegating it to freight forwarders without verification, assuming domestic determinations apply internationally, or optimizing for duty savings without regard for defensibility—create costs and risks that compound over time. TechCharge's experience demonstrates how a seemingly minor classification decision can cascade into substantial financial loss, relationship damage, and ongoing operational burden.

Companies that build classification discipline into their export operations gain competitive advantage. Accurate classification prevents the direct costs of reassessment, fines, and storage. It prevents the indirect costs of delays, damaged relationships, and enhanced scrutiny. It creates predictable, reliable logistics that support business growth rather than constraining it.

This discipline requires investment. Expert consultation costs money. Verification processes take time. Documentation requirements add overhead. But these investments pay returns through avoided problems—returns that often exceed the investments many times over.

The six digits of an HS code represent more than administrative data. They represent your understanding of your products, your respect for destination market requirements, your compliance culture, and your operational professionalism. Get them right, and you've built a foundation for successful international trade. Get them wrong, and you've created problems that will find you eventually, usually at the worst possible time.

Classification accuracy isn't just compliance. It's competitive strategy. Treat it accordingly.

NOVEMBER 27, 2025

NOVEMBER 27, 2025

NOVEMBER 27, 2025

NOVEMBER 27, 2025

NOVEMBER 27, 2025